He spends much of the book following (or stalking) a woman he knows as Sóla G-, because at one moment during a screening of The Vampires she stood up and her features merged perfectly with those of Musidora as Irma Vep.

Sleeping, he dreams variations on the films, in which the web of incident is interwoven with strands from his own life.Īnd reading, we see the cinema breaking into his reality: an epistemic disruption. When not spooling them into himself through his eyes, he is replaying them in his mind. As a rule, he goes to both cinemas on the same and sees most films as often as he can.” He pays for this by turning tricks in what passes for Reykjavik’s cruising scene - a furtive, improvised and ultimately dangerous career.Īnd now the boy lives in the movies. “The boy watches all the films that are imported to Iceland. Reykjavík has two cinemas, the Old and the New, each showing one or two films a day, then three on Sundays. He is a young man on the fringes of a society that is itself on the fringes of the world” - that is, Reykjavík, 1918, shortly before Icelandic independence, just as the Spanish flu arrives, and all while the volcano Katla is painting the skies a lurid red.Īnd he watches a lot of films. To quote Moonstone’s blurb, Máni Steinn, our 16-year-old protagonist, “is queer in a society where the idea of homosexuality is beyond the furthest extreme. Which isn’t to say that hallucinations, even when known as such, can’t mess you up completely. That, perhaps, would be a good reason to start screaming: because something very not real is happening for the very first time. That is, instead of an engagement with something ‘real’, to watch a film is to respond to something clearly and (hopefully) interestingly not real. Ineluctable snobbery of the intellectual: hon hon hon, see the great unwashed scattering! Before a simple moving image! Les buffoons.Īnd besides, it always seemed to me to miss the point of cinema.

No heat from the steam, no smell of oil, no whirl of the wind as a great catastrophe of physics comes clattering close.

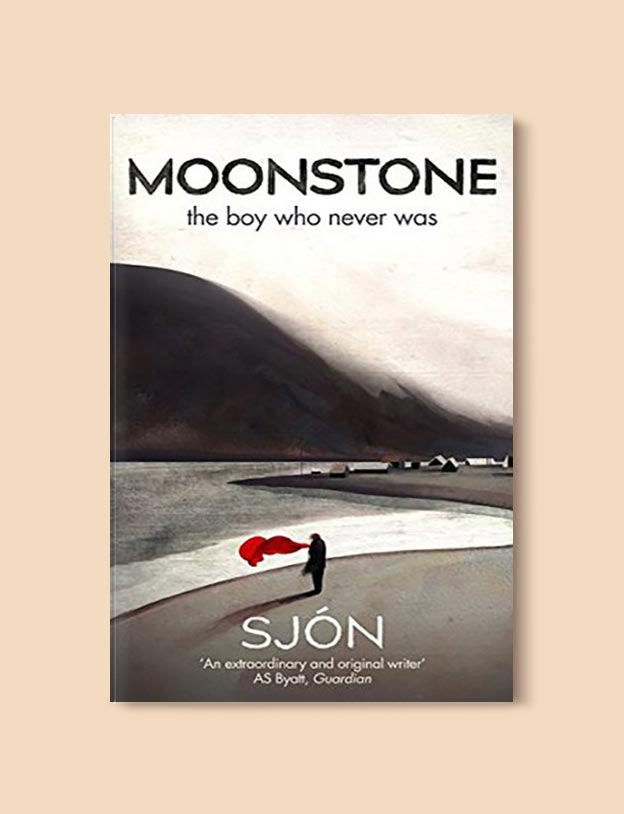

No juddering rumble of the train getting closer. Always irritated me, and I was immensely gratified when I first heard that it was almost certainly not true. You know that story of the early French cinemagoers? The ones who stampeded when they saw a train coming towards them, apparently in fear that they were all going to get squashed. Moonstone by Sjón, translated by Victoria Cribb (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2016)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)